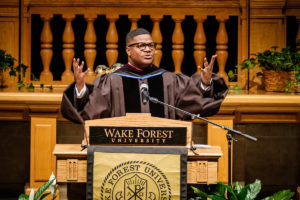

2020 Keynote: Lest We Forget

Delivered by Dean of the School of Divinity Jonathan L. Walton on Feb. 20, 2020

A reading from James Baldwin excerpted from “Down At the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind.”

I rushed home from school, to the church, to the altar, to be alone there, to commune with Jesus, my dearest Friend, who would never fail me, who knew all the secrets of my heart. Perhaps He did, but I didn’t, and the bargain we struck, actually, down there at the foot of the cross, was that He would never let me find out.

He failed His bargain. He was a much better Man than I took him for.

People love to quote the Bible. People who do not necessarily know the Bible, love to quote the Bible. Whenever we want to affirm what has become a cultural truism in our society— Whenever we want to enchant proverbial sayings with sole authority—there is no better place to park a saying than within the pages of scripture.

When someone wants to encourage self-reliance or justify their indifference to the plight of others, we hear, “The Bible says, ‘God helps those who help themselves.”

No, it does not. One will not find that phrase anywhere in scripture. It comes from the pen of 17th century English philosopher Algernon Sydney and then later popularized by Benjamin Franklin in his Poor Richard’s Almanac.

When we want to defend corporal punishment, the spanking of children, we say, “The Bible says spare the rod and spoil the child.”

No, it does not. This phrase came from a satirical poem by Samuel Butler in the 17th century. Butler was mocking the piety of the Puritans and Presbyterians alluding to an erotic relationship, not hardly Christian formation.

Such examples reveal how many of us comfortably and uncritically accept that which is passed down to us. These examples show the ways we accept “tradition” as sacred Truth, folk wisdom as metaphysical fact.

There is one other. It is a familiar saying among those of us with evangelical roots. “The Bible says God will cast our sins into the sea of forgetfulness, never to be brought against you again.”

Well, guess what? No, it does not. Though we can identify a line in Micah where the Hebrew prophet speaks of casting sins into the sea, the extension of forgetfulness is nowhere in the text. It was probably a theological turn-of-phrase of a gifted preacher somewhere—a phrase that we have passed down from one generation to another.

Though this saying may have served as a creative, constructive turn for some, the whole notion of forgetting one’s sins strikes others as theologically problematic. Time can prove a productive pedagogical lens. History can be a great teacher. The past is prologue. To live honestly in the present and responsibly for the future is to wrestle with one’s past. This is why, in the sentiment of James Baldwin, any attempt to erase the past as if it is some form of salvation is folly. Forgetting the past is not emancipation. It is amnesia. It is not deliverance. It is a form of dementia.

This is how the ancient Greeks viewed the erasure of history. In Greek mythology, the River Lethe flowed through Hades, the underworld. Lethe means concealment, and anyone who drank its waters had their memory erased as an eternal punishment.

Socrates cites this river in Book X of Plato’s Republic. Socrates teaches Glaucon that each soul in the afterlife has an opportunity to reincarnate into a new body. One would think these souls would learn from their previous experiences to become a more righteous being, particularly for those who were unapologetically brutal and blameworthy in an earlier life. Passing through the torturous underworld of Hades should have set them straight. However, before returning to life, self-indulgent souls drank too much from the River Lethe. The waters concealed their past. The waters erased the potential lessons of the afterlife. Unrighteous souls were doomed to repeat history rather than learn from it.

I understand that we live in a society that interprets progress as relinquishing the past. We are a forward-thinking, futuristic oriented nation—mainly when it serves our purposes. “What’s done is done. Let’s close that book and move on,” some say. “We are autonomous moral subjects—free to make our own choices and decisions,” others believe. If only this were true.

All of us are actors on the stages of history—our scenes and settings were established well before our entrance. Each of us is informed by the legacies, logic, and language of those who lived before us. We are all shaped by the people, practices, and precedents established prior to our birth.

For instance, today, we have prospective Divinity School students visiting campus. These students, most in their mid-twenties, are interested in our campus because of the progressive vision of many assembled here today. Over three decades ago, when our Baptist brethren elected to drop their anchors in the harbors of gender exclusion and anti-intellectualism, some on this campus had a vision of a different kind of divinity school. You envisioned a divinity school that welcomed those that the Southern Baptist denomination rejected, a divinity school that would develop those who the Southern Baptist faith demonized. We are the beneficiaries of that vision. We aim to extend this legacy of inclusion and acceptance. This is our history. It is a beautiful history. It beckons brilliant minds to come to Wake Forest.

Nevertheless, we must also acknowledge that our history at Wake Forest is both beautiful and terrible. Noble and tragic. Honorable and despicable. We owe our very existence, in part, to the exploited lives and enslaved labor of people of African descent. Men and women like Isaac, Pompie, Caroline, and Lucy sold from the John Blount estate in 1860, precious people whose humanity was sacrificed to prepare young, white Baptist men for the ministry. Baptist young men whose conception of Christ supported America’s serpentine system of slavery. Men whose theology was a religion of white supremacy. Campus officials who sold off human beings like metal tools or farm animals.

Such narratives are a part of our institutional DNA. Profits from the sale of human beings constitute the institutional soil in which our existence is rooted. And the fact that we were not present in the mid-19th century does not separate us from the social, political, and economic legacies of our Founders’ decisions. The fact that our particular families may not have enslaved others does not place us outside of the historical frame of inequality and opportunity that continues to shape our society.

Each one of us stands on the sun-baked, bruised shoulders of those who built this school against their will. We can delude ourselves into believing that we all deserve what history has bequeathed us. To do so, however, would be to drink from the River Lethe, conceal central aspects of our past, and collude in a conspiracy of silence concerning past transgressions.

Hence, this moment in the life of our University calls for neither denial nor defensiveness. The question of whether you are “guilty” of past indiscretions is a luxury we can no longer afford. We must subsume that question under our willingness to take responsibility for our current state of affairs.

Similarly, as members of this community, none of us has the privilege to claim innocence regarding the past—not even me, a product of ancestors enslaved in this state of North Carolina. If we do, our pleas of innocence will only constitute a further crime. We owe this institution and ourselves more. You and I must muster the moral courage and intellectual candor to craft a more inclusive and thus more productive future. In the words of Maya Angelou, “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

Unconcealing Truth is the only way for us to progress. The Greeks had a lesson here, too. If Lethe was the river of or Goddess of concealment, Aletheia was the Goddess of Truth or unconcealment. There is an instructive story about her origins. Legend states that the great artisan Prometheus crafted Aletheia. He used all of his skills so that Aletheia might guide and shape human behavior. When Prometheus had to leave his workshop, his apprentice Dolus decided to forge his own Goddess–a goddess that would look just like the Goddess of Truth. But Dolus ran out of clay right when he got to her feet. Upon Prometheus’s return, he was amazed at Dolus’s creation. Prometheus could not even distinguish between his real creation and Dolus’s forgery. So he infused them both with life and summoned them. Aletheia, the Goddess of Truth, took measured steps forward. Her deceptive twin, a twin that Prometheus named Mendacium, remained stuck in the same place.

A reality built on a lie may appear successful, but mendacity has a deficient foundation. Only Truth will move us productively forward. Only Truth will liberate us from the demons of our past. Only Truth will provide us a firm foundation to stand with and for humanity. Only the Truth will ultimately set us free.